Getting Started

pip3 install pyrtl or pip install pyrtl

PyRTL Features

PyRTL provides a collection of classes for Pythonic register-transfer level design, simulation, tracing, and testing suitable for teaching and research. Simplicity, usability, clarity, and extensibility rather than performance or optimization is the overarching goal. Features include:

- Elaboration-through-execution, meaning all of Python can be used including introspection

- Design, instantiate, and simulate all in one file and without leaving Python

- Export to, or import from, common HDLs (BLIF-in, Verilog-out currently supported)

- Examine execution with waveforms on the terminal or export to a .vcd as projects scale

- Elaboration, synthesis, and basic optimizations all included

- Small and well-defined internal core structure means writing new transforms is easier

- Batteries included means many useful components are already available and more are coming every week

New in 0.8.7: SimCompiled provides seamless JIT to C for simulation performance, new hardware modules for PRNG, fixes for lots of issues with Verilog generation (support for memory and testbench generation both improved significantly), convenience functions for integer log2 and truncate, and even more examples in the documentation.

Here are some simple examples of PyRTL in action. These examples implement the same functionality as those highlighted in the wonderful related work Chisel, which in turn allows us to see the stylistic differences between the approaches.

A finite impulse response filter -- this function generates a sequential curcuit that grabs input x and a list of coefficientsbs. If one looks to the

Wikipedia FIR description you can see that list zs is the registers required

to implement the delay. The function returns an output y which is the resulting sum of products and is valid every cycle (since the design is naturally fully

pipelined). The code below the fir function is everything needed to instantiate, simulate, and visualize the resulting design.

import pyrtl

def fir(x, bs):

rwidth = len(x) # bitwidth of the registers

ntaps = len(bs) # number of coefficients

zs = [x] + [pyrtl.Register(rwidth) for _ in range(ntaps-1)]

for i in range(1,ntaps):

zs[i].next <<= zs[i-1]

# produce the final sum of products

return sum(z*b for z,b in zip(zs, bs))

x = pyrtl.Input(8, 'x')

y = pyrtl.Output(8, 'y')

y <<= fir(x, [0, 1])

sim = pyrtl.Simulation()

sim.step_multiple({'x':[0, 9, 18, 8, 17, 7, 16, 6, 15, 5]})

sim.tracer.render_trace()

A greatest common demoninator calculator -- this function generates a sequential curcuit that grabs inputs a and b when e goes high,

and then, while e is low, calculates the GCD through iterative subtraction. The function returns two "wires", one which will hold the value

when it is ready, and the other which is a boolean ready signal.

from pyrtl import *

def gcd(a, b, begin):

x = Register(len(a))

y = Register(len(b))

done = WireVector(1)

with conditional_assignment:

with begin:

x.next |= a

y.next |= b

with x > y:

x.next |= x - y

with y > x:

y.next |= y - x

with otherwise:

done |= True

return x, done

MaxN generates hardware that take N inputs and calculates the max of them. This example makes use of Python's notation

for handling multiple inputs which packs them nicely into a list for you. It is also a nice demonstration that the full power of

Python is available to you in PyRTL including functional tools like reduce (here chaining together multiple max2 elements into a

bigger maxN), map, recursion, lambdas, etc.

from pyrtl import *

from functools import reduce

def max_n(*inputs):

def max_2(x,y):

return select(x>y, x, y)

return reduce(max_2, inputs)

Mul generates a small 4 x 4 multiplier with a simple table lookup. The first line simple checks that the inputs are each 4-bits wide. The next is a Python function that gives us the values we want stored in the ROM as a function of the address. The ROM is automatically initialized with that function. The final hardware generated simply concatenates the two 4-bit inputs into an single 8-bit address and returns the value at that ROM address.

from pyrtl import *

def mul(x, y):

assert(len(x) == 4 and len(y) == 4)

romdata = lambda addr: (addr >> 4) * (addr & 0xf)

tbl = RomBlock(8, 8, romdata)

return tbl[concat(x,y)]

The classic ripple-carry adder -- this function generates a ripple carry adder of abitrary length including both carry in and carry out.

The full adder (fa) takes 1-bit inputs and produces 1-bit outputs. We iteratively generate full adders and link the carry in of each

new adder to the carry out of the prior. A Python dictionary keeps track of the wires carrying the sum bits as we iterate through. The final

sum is then just the concatenation of the wires in that dictionary.

from pyrtl import *

def fa(x, y, cin):

sum = x ^ y ^ cin

cout = x&y | y&cin | x&cin

return sum, cout

# An n-bit ripple carry adder with carry in and carry out

def adder(a, b, cin):

a, b = match_bitwidth(a, b)

n = len(a)

sum = {}

for i in range(n):

sum[i], cout = fa(a[i], b[i], cin)

cin = cout

full_sum = concat_list([sum[i] for i in range(n)])

return full_sum, cout

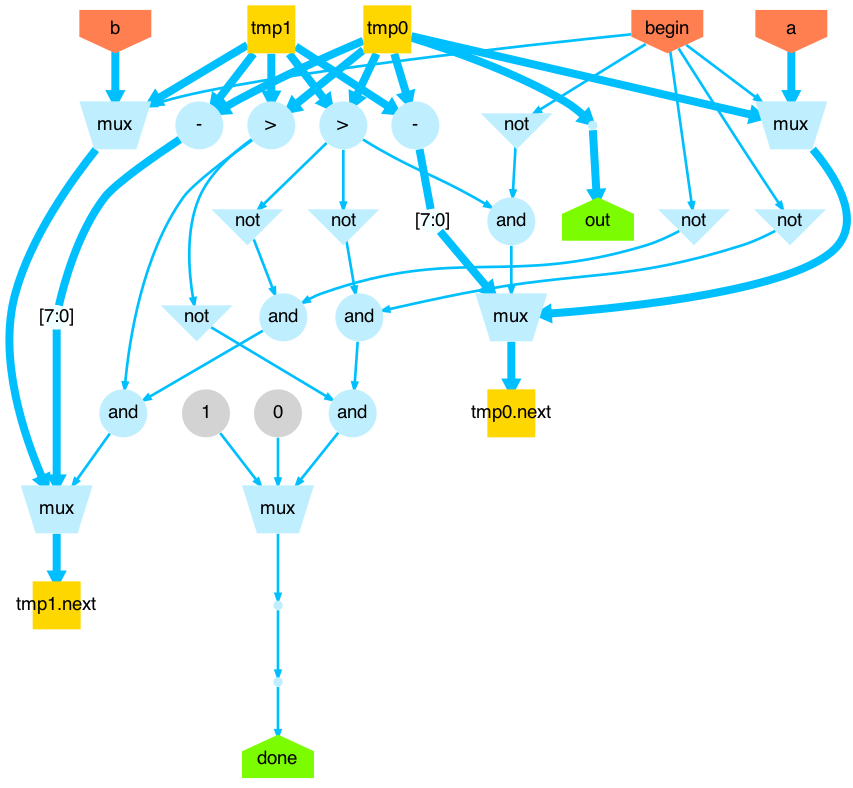

PyRTL can also produce visualizations of your design with block_to_svg(), such as this graph of the GCD sequential circuit described previously:

The 10,000 Foot Overview

At a high level PyRTL builds the hardware structure that you explicitly define. If you are looking for a tool to take your random Python code and turn it into hardware, you will have to look elsewhere -- this is not HLS. Instead PyRTL is designed to help you concisely and precisely describe a digital hardware structure (that you already have worked out in detail) in Python. PyRTL restricts you to a set of reasonable digital designs practices -- the clock and resets are implicit, block memories are synchronous by default, there are no "undriven" states, and no weird un-registered feedbacks are allowed. Instead, of worrying about these "analog-ish" tricks that are horrible ideas in modern processes anyways, PyRTL lets you treat hardware design like a software problem -- build recursive hardware, write instrospective containers, and have fun building digital designs again!

To the user it provides a set of Python classes that allow them to express their

hardware designs reasonably Pythonically. For example, with WireVector you get a structure that acts very

much like a Python list of 1-bit wires, so that mywire[0:-1] selects everything except the

most-significant-bit. Of course you can add, subtract, and multiply these WireVectors or concat multiple

bit-vectors end-to-end as well. You can then even make normal Python collections of those WireVectors and

do operations on them in bulk. For example, if you have a list of n different k-bit WireVectors (called x) and you

want to multiply each of them by 2 and put the sum of the result in a WireVector y, it looks like

the following: y = sum([elem * 2 for elem in x]). Hardware comprehensions are surprisingly useful. Below we get into

an example in more detail, but if you just want to play around with PyRTL

try Jupyter Notebooks on any

of our examples on MyBinder.

Hello N-bit Ripple-Carry Adder!

While adders are a builtin primitive for PyRTL, most people doing RTL are familiar with the idea of a Ripple-Carry Adder and so it is useful to see how you might express one in PyRTL if you had to. Rather than the typical Verilog introduction to fixed 4-bit adders, let's go ahead and build an arbitrary bitwidth adder.

def one_bit_add(a, b, carry_in):

assert len(a) == len(b) == 1 # len returns the bitwidth

sum = a ^ b ^ carry_in # operators on WireVectors build the hardware

carry_out = a & b | a & carry_in | b & carry_in

return sum, carry_out

def ripple_add(a, b, carry_in=0):

a, b = pyrtl.match_bitwidth(a, b)

if len(a) == 1:

sumbits, carry_out = one_bit_add(a, b, carry_in)

else:

lsbit, ripplecarry = one_bit_add(a[0], b[0], carry_in)

msbits, carry_out = ripple_add(a[1:], b[1:], ripplecarry)

sumbits = pyrtl.concat(msbits, lsbit)

return sumbits, carry_out

# instantiate an adder into a 3-bit counter

counter = pyrtl.Register(bitwidth=3, name='counter')

sum, carry_out = ripple_add(counter, pyrtl.Const("1'b1"))

counter.next <<= sum

# simulate the instantiated design for 15 cycles

sim_trace = pyrtl.SimulationTrace()

sim = pyrtl.Simulation(tracer=sim_trace)

for cycle in range(15):

sim.step({})

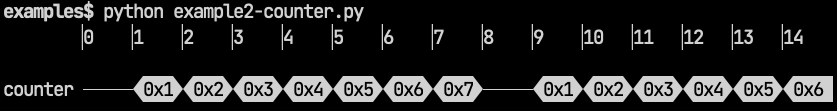

sim_trace.render_trace()The code above includes an adder generator with Python-style slices on wires (ripple_add), an instantiation

of a register (used as a counter with the generated adder), and all the code needed to simulate the design,

generate a waveform, and render it to the terminal. The way this particular code works is described more in

the examples/ directory. When you run it, it should look like this (you can see the counter going from 0 to 7 and repeating):

A Few Gotchas

While Python is an amazing language, DSLs in Python are always forced to make a few compromises which can sometimes catch users in some unexpected ways. Watch out for these couple of "somewhat surprising features":

PyRTL never uses any of the "in-place arithmetic assignments" such as

+=or&=in the traditional ways. Instead only<<=and|=are defined and they are used for wire-assignment and conditional-wire-assignment respectively (more on both of these in the examples). If you declare ax = WireVector(bitwidth=3)andy = WireVector(bitwidth=5), how do you assignxthe value ofy + 1? If you dox = y + 1that will replace the old definition ofxentirely. Instead you need to writex <<= y + 1which you can read as "xgets its value fromy + 1".The example above also shows off another aspect of PyRTL. The bitwidth of

yis 5. The bitwidth ofy + 1is actually 6 (PyRTL infers this automatically). But then when you assignx <<= y + 1you are taking a 6-bit value and assigning it to 3-bit value. This is completely legal and only the least significant bits will be assigned. Mind your bitwidths.PyRTL provides some handy functions on WireVectors, including

==and<which evaluate to a new WireVector a single bit long to hold the result of the comparison. The bitwise operators&,|,~and^are also defined (however logic operations such as "and" and "not" are not). A really tricky gotcha happens when you start combining the two together. Consider:doit = ready & state==3. In Python, the bitwise&operator has higher precedence than==, thus Python parses this asdoit = (ready & state)==3instead of what you might have guessed at first! Make sure to use parentheses when using comparisons with logic operations to be clear:doit = ready & (state==3).PyRTL right now assumes that all WireVectors are unsigned integers. When you do comparisons such as "<" it will do unsigned comparison. If you pass a WireVector to a function that requires more bits that you have provided, it will do zero extension by default. You can always explicitly do sign extension with

.sign_extended()but it is not the default behavior for WireVector. For now, this is for clarity and consistency, although it does make writing signed arithmetic operations more text heavy.

Related Projects

Amaranth (previously nMigen) is another python hardware project providing an open-source toolchain that has a lot of wonderful stuff for working with FPGAs in particular. It has support for evaluation board definitions, a System-on-Chip toolkit, and more. I think it has a similar philosophy of trying to be easy to learn and use and simplify the design of complex hardware with reusable components. Amaranth (at the time of writing) has much better support on the back end for a variety of real devices and low level stuff like managing clock domains, but PyRTL I think it provides some value in getting going right in the command line and how it handles memories etc. I would be eager to see the power of these tools combined in some way!

Chisel is a project with similar goals to PyRTL but is based instead in Scala. Scala provides some very helpful embedded language features and a rich type system. Chisel is (like PyRTL) a elaborate-through-execution hardware design language. With support for signed types, named hierarchies of wires useful for hardware protocols, and a neat control structure call "when" that inspired our conditional contexts, Chisel is a powerful tool used in some great research projects including RISC-V. Unlike Chisel, PyRTL has concentrated on a simple to use and complete tool chain which is useful for instructional projects, and provides a clearly defined and relatively easy-to-manipulate intermediate structure in the class Block (often times call pyrtl.core) which allows rapid prototyping of hardware analysis routines which can then be codesigned with the architecture.

SpinalHDL is a different approach to HDL in Scala and is very much aligned with the way PyRTL is built (invented independently it is neat to see the convergent evolution which, I think, points to something deeper about hardware design). It has a lot of support and really well thought out structures.

MyHDL is another neat Python hardware project built around generators and decorators. The semantics of this embedded language are close to Verilog and unlike PyRTL, MyHDL allows asynchronous logic and higher level modeling. Much like Verilog, only a structural "convertible subset" of the language can be automatically synthesized into real hardware. PyRTL requires all logic to be both synchronous and synthesizable which avoids a common trap for beginners, it elaborates the design during execution allowing the full power of Python in describing recursive or complex hardware structures, and it allows for hardware synthesis, simulation, test bench creation, and optimization all in the same framework.

Yosys is an open source tool for Verilog RTL synthesis. It supports a huge subset of the Verilog-2005 semantics and provides a basic set of synthesis algorithms. The goals of this tool are quite different from PyRTL, but the two play very nicely together in that PyRTL can output Verilog that can then be synthesized through Yosys. Likewise Yosys can take Verilog designs and synthesize them to a very simple library of gates and output them as a "blif" file which can then be read in by PyRTL.

PyMTL3 (a.k.a. Mamba) is an beta stage an "open-source Python-based hardware generation, simulation, and verification framework with multi-level hardware modeling support". One of the neat things about this project is that they are trying to allow simulation, modeling, and verification at multiple different levels of the design from the functional level, the cycle-close level, and down to the register-transfer level (where PyRTL really is built to play). Like MyHDL they do some meta-programming tricks like parsing the Python AST to allow executable software descriptions to be (under certain restrictions -- sort of like Verilog) automatically converted into implementable hardware. PyRTL, on the other hand, is about providing a limited and composable set of data structures to be used to specify an RTL implementation, thus avoiding the distinction between synthesizable and non-synthesizable code (the execution is the elaboration step).

ClaSH is a hardware description embedded DSL in Haskell. Like PyRTL it provides an approach suitable for both combinational and synchronous sequential circuits and allows the transform of these high-level descriptions to low-level synthesizable Verilog HDL. Unlike PyRTL, designs are statically typed (like VHDL), yet with a very high degree of type inference, enabling both safe and fast prototying using concise descriptions. If you like functional programming and hardware also check out Lava.